Month: August 2014

Interviewing Users

Next up on the reading list is Interviewing Users by Steve Portigal. Time for a bit of hands-on (sort of) reading.

Wicked problems – what do designers bring to the table?

Last night I went to listen to Dawn O’Neil, former CEO of beyondblue and Lifeline, deliver a talk – Collective Impact and Social Change – A challenge and an opportunity for the Service Design community. Ms O’Neill’s talk covered some interesting stuff, including:

- an introduction to the Collective Impact Framework

- the Cynefin Framework

- a sense that design was valued for something beyond the aesthetic (hooray).

After the talk I walked away with this question:

At what point do designers actually provide value when organisations are working on complex (or wicked) problems? And how?

I thought I’d take some time today to try and answer my own question.

Ms O’Neill’s talk showed an enthusiasm and understanding that design can be a valuable tool when tackling big, hairy social problems.

Her talk began with an overview of two frameworks that have helped inform her own approach to leading organisations involved in tackling this problems.

The Cynefin Framework

The Cynefin Framework is a sensemaking framework. It’s useful for identifying:

- what type of problem you are working on

- how you should approach this problem.

The Collective Impact Framework

When you’re working on complex problems the Collective Impact Framework is a useful approach. The Collective Impact Framework sets out the following requirements for working on a complex problem:

- Common Agenda

- Shared measurement

- mutually reinforcing activities

- Continuous communication

- A backbone organisation – an organisation dedicated to coordinating the effort.

There are also three prerequisites:

- An influential champion

- Financial resources

- Urgency for change (the ‘burning platform’)

There’s a lot more about Collective Impact here at http://www.collaborationforimpact.com/

Collective Impact was first described by Stanford Social Innovation Review here http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/collective_impact

Discussions and case study

After discussion about the frameworks we broke off into smaller groups to work through a case study about an indigenous community. I’ve paraphrased the case study below. This is the general gist. It’s definitely not the whole case study though.

Money has been poured into an indigenous community from different government oragencies for decades without any tangible change. The community elders have identified they want to improve the opportunities for younger community members. Violence, incarceration, lack of employment and homelessness have been identified by the elders as key issues for the community’s young people. How would you approach this task, as a group?

When the different groups shared their approaches at the end of the evening I realised that there were probably more community development workers, and other NFP types, in the room than design practitioners (I think).

Community development – what is it anyway?

My partner Eilis, is a community development practitioner, so I felt like I had a basic understanding of what community development is (mostly obtained via osmosis and nodding). I already knew that community development and human-centred design share some pretty fundamental similarities in philosophy.

But what are the differences? Why engage designers on a project if community development workers are already there, doing the same work?

So, what do designers add?

Where community development and design overlaps

1. Both practices share similar philosophies and visions. People first, human-focused.

2. Community development workers and designers are not the subject-matter experts. We both work to uncover the problem and frame the problem.

3. We both focus on positive change for people.

4. We both use tools and frameworks to engage with, and understand, people.

How designers are different (what we bring that’s unique)

When we listened to other groups present their response to the case study last night, there were a couple of things I noticed. Here’s a few examples of how groups had responded to the case study.

“I already know that one problem facing indigenous people is availability of food, so we’d work on that by doing these things …”.

“We’d bring in young mentors from other indigenous communities to mentor the young people.”

There were quite a few other responses like this.

These approaches may be very good approaches (they sound logical to me), but these approaches weren’t derived from a design process.

Designers work with assumptions

Designers validate their assumptions. They don’t start designing solutions until they have:

- completed some form of research (usually ethnographic research)

- identified themes and patterns that have presented during the research

- understood the problem.

For a designer pre-existing knowledge about an issue is only an assumptions until this knowledge has been tested and validated by the people you are designing for.

Following these processes are important because they help us mediate our own biases.

Human-centred design process

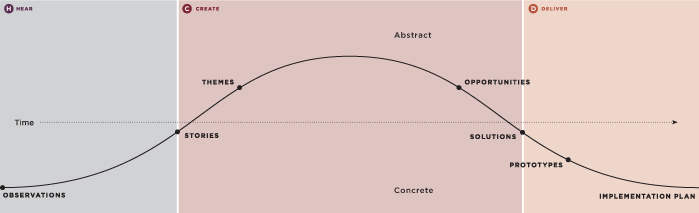

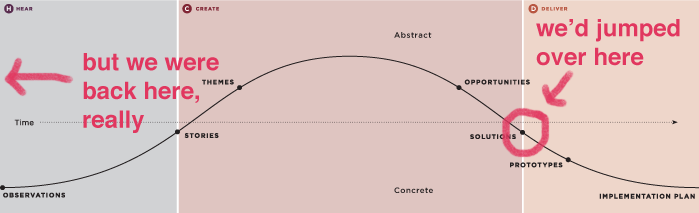

Here’s how IDEO maps that human-centred design process.

So I think this is how designers (or design-thinking) may add value.

This quote from Wicked Problems also supports (I think) the approach for validating our pre-existing knowledge about an issue.

Wicked problems have no definitive formulation. The problem of poverty in Texas is grossly similar but discretely different from poverty in Nairobi, so no practical characteristics describe “poverty.”

Please keep in mind, my intention here isn’t to be critical of community development, but instead to identify what designers offer that make them valuable. I reckon designers have a lot to learn from community development. And if you agree, or disagree, I would love to hear your thoughts on this.