Today I was invited to critique a design critique. It’s a little meta.

Who critiqued my critique of the critique? Probably everyone, once they closed the security doors behind them and they had disappeared into their lovely air conditioned offices.

It was nice to be asked to this critique because:

a. It’s nice to be asked to anything, really. Especially when there’s catering.

b. It’s nice to be around established design practitioners because they know more than me and I can steal their knowledge!

The design critique framework

I’ve never been a huge fan of frameworks because they remove all creativity and spontaneity and thinking from the job. Don’t be constrained by frameworks. Knowledge workers, be free!

Except this is ridiculous and exhausting mainly because you have to be all creative and spontaneous and do thinking and it turns out frameworks are just a bunch of rules you start with, and you can change them as you go anyway if something better becomes apparent.

It’s nice to have a framework.

The other dude there critiquing the critique had a framework his team uses which was very good.

I have my own framework, honed from years of being bashed about by critiques and wondering why people were so unkind.

Here’s my design framework critique:

1. We must both be willing participants in the critique.

You can’t look over my shoulder and say “that should be moved 10 pixels to the left, you know”. That is not critique. That is being annoying.

2. Start with questions

Here’s a few examples to show what I mean:

- why are you asking for a critique?

- what do you need from this critique?

- what business problem are you solving?

- what type of users are you designing for?

- what kind of constraints are you working with?

- why did you do it that way?

This does two things.

1. It sets the scene for you as the critiquer.

2. It also displays a bit of professional courtesy, I think.You trust me enough not to assume I am a dumb arse. It’s nice not to allude to your colleague being a dumb arse! Unless you want to. Then you should. There isn’t enough people calling other people dumb arses in business settings, but you can only do this to their face, then fight it out and make up. Don’t do it behind their backs.

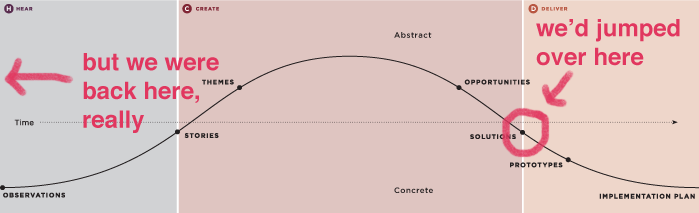

3. If it’s at the start of the design process go big, if it’s two weeks from final design go small and detailed, if it’s two days from final design too late just a hug will do (don’t touch me)

If you critique the basic assumptions I made in week 1 but now it’s week 12 you are most probably right and time will prove that you are the better designer and probably also a nicer person but you are serving no real purpose by critiquing that so say it quietly so I don’t hear. Unless I say something like, “It’s all gone horribly wrong. Where did I go wrong in week 1?” then go for it.

Bring that stuff up in the retrospective.

4. Don’t solve it for me

There are many ways to design something, and this is both magical and really fucking annoying. Either way, don’t give me the answer because then you’ve given me the answer but you haven’t really made go through the process to get to the answer and I’ll have to ask you again next time. You’ve caught me a fish but you haven’t taught me how to fish. Fishing is very boring, but it is necessary unless you live near a supermarket where you can just go buy a fish. Be careful with Woolies fish though. Not particularly fresh.

Bonus: Why ask for a critique anyway?

We all have biases and blind spots and every now and then it’s nice to be reminded that we have biases and blind spots. Actually, no it’s not. It’s awful to be reminded of this. Do it anyway. Your employer will thank you.

To be honest I’m not sure if this technically is a framework, or just a list of questions, but I think it’s a framework because I don’t truly know what a framework is. Just quietly, I don’t think the other people who talk about their frameworks actually know what frameworks are either. Isn’t life odd.

This is all very nice but it’s not about the design critique. What happened there.

Some very clever people sat in a room and gave good and respectful feedback to a new designer and it was nice to hear their feedback, because feedback from so many different angles brings up lots of different aspects of a design (or design process).

Can you be more specific?

Not really. No.